- Home

- Vanda Krefft

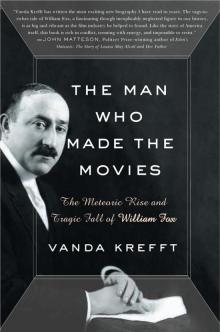

The Man Who Made the Movies

The Man Who Made the Movies Read online

DEDICATION

To the late Angela Fox Dunn, the keeper of the flame

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: “The Biggest Deal in Motion Picture History”

Part I: Beginnings, 1879–1903

Chapter 1: Promises

Chapter 2: Destiny

Chapter 3: Eva

Chapter 4: The Dark Side of the Dream

Part II: The Greatest Adventure, 1904–1925

Chapter 5: 700 Broadway

Chapter 6: Necessary Expenses

Chapter 7: “The Next Napoleon of the Theatre”

Chapter 8: The Wizard of Menlo Park

Chapter 9: Madness and Murder

Chapter 10: Justice

Chapter 11: Independence

Chapter 12: “William Fox Presents”

Chapter 13: A Daughter of the Gods (1916)

Chapter 14: “The Greatest Showman on Earth”

Chapter 15: Mirror of the Movies

Chapter 16: “All His Secret Ambition”

Chapter 17: “The Finest in Entertainment the World Over”

Chapter 18: “The Making of Me”

Chapter 19: The End of Theda

Chapter 20: Exodus

Chapter 21: Everything Changes

Chapter 22: A Visit from Royalty

Chapter 23: Eclipse

Chapter 24: “Humanity Is Everything”

Chapter 25: The Iron Horse (1924)

Part III: The One Great Independent, 1925–1929

Chapter 26: Renewal

Chapter 27: “The Wonder-Thing”

Chapter 28: Talking Pictures

Chapter 29: All for Fox Films

Chapter 30: The Roxy

Chapter 31: Sunrise (1927)

Chapter 32: The Triumph of Movietone

Chapter 33: The One Great Independent

Chapter 34: Storm Signals

Chapter 35: Lone Master of the Movies

Chapter 36: Big Money

Chapter 37: Trouble

Chapter 38: Fate

Chapter 39: Recovery

Chapter 40: Disaster: October 1929

Chapter 41: Siege

Chapter 42: War

Chapter 43: “We Want You, Mr. Fox”

Chapter 44: Defeat

Chapter 45: The End of the Dream

Part IV: Despair, 1930–1943

Chapter 46: Sorrow and Rage

Chapter 47: The Meter Reader and the Banker

Chapter 48: Upton Sinclair Presents William Fox

Chapter 49: Nobody

Chapter 50: Alone

Chapter 51: Revenge

Chapter 52: Confession

Chapter 53: Prison

Part V: Acceptance, 1943–1952

Chapter 54: Exile

Chapter 55: Fade to Black

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Notes

Index

Photograph Section

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

“The Biggest Deal in Motion Picture History”

In the sunny, unusually warm early afternoon of Sunday, March 3, 1929, despite the competing call of preparations for Herbert Hoover’s inauguration the following day in Washington, DC, reporters from major newspapers and entertainment trade publications made their way over to the Roxy Theatre at Fiftieth Street and Seventh Avenue. Known as “the Cathedral of the Motion Picture,” the $12 million Roxy was the world’s largest and most spectacular movie theater, with 5,920 seats and staggeringly lavish appointments.

Past the half-block-long ochre-and-slate-colored Spanish Baroque façade, under the marquee that blazed nightly with the power of 4,500 bulbs, the reporters filed in through the entrance to the Roxy’s ticket vestibule. A little farther beyond lay the outer court of the Roxy’s splendid fantasy world: a five-story lobby rotunda bordered by green marble columns and ornamented with wine-colored hanging draperies, gold leaf wall decoration, deep pile carpeting, and a one-and-a-half-ton crystal chandelier. Farther still was the palatial theater itself, with its 110-piece symphony orchestra pit, three massive organ consoles, and ornate proscenium arch. Along with a movie, the Roxy’s bill of fare included symphony orchestra performances, dance recitals, newsreels, and live theater vignettes.

Today, however, the big story would not take place on the Roxy’s stage or screen. Up the executive elevator the reporters rode, past the fully equipped nurses’ station and above the basement electrical plant capable of generating enough power for a city of twenty-five thousand. Exiting at the fifth floor, they headed for the private screening room to wait for William Fox, founder of Fox Film and Fox Theatres and owner of the Roxy. Some reporters flopped into the easy chairs scattered around the room. Others lounged against the grand piano, which was piled high with hats and coats. A table held light refreshments.

Was it really true?

Three days earlier, on Thursday, February 28, 1929, Film Daily had run a front-page article headlined “Fox Buys Loew’s, M-G-M.” The text began, “The biggest deal in motion picture history has been closed.” According to Film Daily, in an agreement finalized the previous Monday, Fox, whose Fox Film was Hollywood’s third-largest movie studio, had secretly acquired a controlling interest in Loew’s, Inc., a 175-house national theater chain that was also the parent company of M-G-M, Hollywood’s second-most-successful studio. With the American movie industry growing explosively—1928 revenues had doubled those of 1926—Loew’s was a red-hot property. The company had total assets of $109 million and annual profits of $8.6 million, and it owned some of the country’s most prestigious theaters. Almost all of Loew’s venues were Class-A, high-capacity, first-run houses, and not one was a “shooting gallery,” as cheap penny arcades were known. M-G-M, which Loew’s owned entirely, ranked second only to Paramount in assets and boasted stars Greta Garbo, Joan Crawford, Buster Keaton, John Gilbert, Lionel Barrymore, Lon Chaney, William Haines, and Norma Shearer. Moreover, because deceased company founder Marcus Loew had been exceptionally well liked and admired for his integrity, the company enjoyed tremendous goodwill within the industry.

Since Loew’s sudden death from a heart attack in 1927, a large block of the family’s stock had been up for sale. If Fox really had bought Loew’s, Fox Film would instantly vault into first place, knocking aside Paramount, and Fox Theatres would expand to include about eight hundred U.S. houses, surpassing Paramount-Publix as the largest movie theater circuit in the country.

“I have no interest in acquiring the chain. I don’t want to buy it,” Fox had hotly insisted ever since rumors of his interest in Loew’s surfaced several months before.* Yet, in the wake of the Film Daily report, the Fox organization had fallen silent, refusing to either confirm or deny the sale. Other publications, including the New York Times, repeated the rumor of a probable takeover.

Then, one day after the Film Daily article, on Friday, March 1, 1929, Fox Film’s publicity chief sent a ten-word telegram to the editors of all the major daily newspapers, show business trade publications, and press associations: “William Fox will make an important announcement Sunday 2 p.m.” That in itself was news. Fox hadn’t held a press conference in years. Unlike his peers (showboat personalities, most of them), he shunned the public stage. He hated to be interviewed and couldn’t stand to see his picture in the paper. Only his accomplishments, his wonderful movies and his beautiful theaters, deserved attention.

Despite the persistence of the rumors, many considered the deal highly unlikely. Warner Bros. was the front-runner to get Loew’s. The Warners’ bankers, Goldman Sach

s, were reportedly preparing to organize a $200 million holding company to facilitate the acquisition of Loew’s, and by late February, the Warners had purchased a significant block of Loew’s stock at $100 a share from General Motors founder William C. Durant. Anticipating success, many Warner Bros. employees and outside speculators bought heavily into Warner stock.

Still, there was no counting Fox out. Raised in appalling poverty on the Lower East Side, with only a third-grade education, fifty-year-old Fox had transformed $1,666 saved from garment industry sweatshop jobs into an international movie production, distribution, and exhibition empire valued at $120 million. Since his start in 1904 as a small theater owner, he had labored feverishly to transform the raffish, nickel-a-ticket entertainment business into a respected art form and a major industry.

All this Fox had done with single-handed control over his two companies, Fox Film and Fox Theatres, and with remarkably little reliance on the Wall Street financial establishment, which during the 1920s had come to control industrial expansion in America. All the other major studio heads had, on their boards of directors, bankers to whom they were compelled to defer. Fox had relatives, friends, and employees. What he said went. “The lone eagle,” the press nicknamed him.

In his sixth floor Roxy Theatre office, with its thick carpets and several phones on the desk, “the little fox,” as he preferred to think of himself, waited before the press conference. At five foot seven, with a receding hairline, prominent nose, sadly sloping eyes, and thickset torso, Fox was physically unprepossessing, the sort of person one might pass countless times on the street without really noticing him. Had he not owned the company, he might have been hired for one of his movies to play a mourner in a funeral scene or to fill out a crowd as an overall-clad, lunch box–carrying laborer. Today, because it was a Sunday, he was casually dressed, wearing a cashmere sweater instead of his usual custom-tailored suit jacket.

Keeping him company in his office was his second-in-command, Winfield “Winnie” Sheehan, general manager and head of production at Fox Film. A ruddy-faced bulldog type who started his career as a newspaper reporter and then gained prominence as the private secretary to New York City police commissioner Rhinelander Waldo, Sheehan had a gregarious, bon vivant personality. Fox liked him and trusted him. They had known each other for about twenty years. Sheehan was the first person Fox hired when he went into film production, and because, at that time, neither of them knew anything about it, they had learned the business together. Sheehan had turned out to be remarkably clever and effective, if not universally admired.

Fox’s mood was somber. The timing was wrong, all wrong. He had been forced into holding this press conference, and if handled awkwardly, it could have disastrous consequences.

It was true that Fox had bought the Loew family’s 400,000 shares of Loew’s, Inc., and true that he considered the stock to represent a controlling interest in the company even though it amounted to less than one-third of the total 1,334,453 outstanding shares. All the other shares were so widely dispersed that it was highly unlikely any effective coalition could ever be formed against him. It was equally unlikely that anyone would want to form a coalition against him. Fox had always made money for his stockholders.

However, he could not safely reveal any details of the transaction to the press. A takeover of Loew’s still required approval from the U.S. Department of Justice, which would have to decide whether combining the second- and third-largest motion picture companies would unreasonably reduce competition in the industry. Fox thought he had settled the matter weeks earlier. Before buying the Loew family’s stock, he had traveled to Santa Fe, New Mexico, to meet with William “Wild Bill” Donovan, the assistant attorney general in charge of antitrust. At that time, Donovan was widely expected to become Hoover’s new U.S. attorney general. Donovan assured Fox that he would not object to the Loew’s stock purchase.

But now Donovan was not going to become attorney general. On February 27, four days before Fox’s press conference, the New York Times reported that Hoover had abruptly switched his choice to the Justice Department’s second-ranked official, Solicitor General William D. Mitchell. Mitchell had no obligation to retain any of his predecessor’s staff or to honor any informal assurances given by them. Fox was frantically trying to assess Mitchell’s views. On this very day, March 3, 1929, a Fox Movietone newsreel crew was in Washington, DC, recording a statement of “philosophy” by Mitchell. How much would Mitchell want to make his own mark? Fox would have to proceed very cautiously. If he were to come across today as bragging, Mitchell might rear up and oppose the Loew’s deal.

And if Mitchell decided against him, Fox would be ruined. Toward the stock’s $50 million purchase price, he had secretly borrowed $27 million—$15 million from AT&T and $12 million from the Halsey, Stuart banking firm. Both loans would fall due by April 1, 1930. Fox had planned to refinance the debt by merging the Fox companies with Loew’s and selling stock in the new behemoth corporation. If there were no merger, there could be no stock sale. Yet Fox had nowhere else to go for the money. He didn’t have $27 million on hand, and the Fox companies couldn’t earn that much in a year. Neither could he simply sell the Loew’s shares to get his money back. On the open market, the shares were worth only about $33.6 million. Fox had paid a high premium ($125 per share compared to a market price of $84) to get such a large block of stock all at once. He also wouldn’t be able to sell the Loew’s shares to any other large studio. If he weren’t able to get government approval for the deal, then neither would anyone else.

And if the acquisition failed, then Fox Film and Fox Theatres would fail, and his life’s work, the driving purpose of his existence, would end.

Not for nothing had Fox once been a stage performer and not for nothing had he already overcome many tremendous challenges. He had started his working life earning eight dollars for a sixty-hour week of manual labor in the garment industry, and people called him “a nut” when he decided to enter the movie business. So far, he had surmounted every obstacle and defeated every adversary. At heart, he was an optimist. One of his early ads read, “There’s a remedy for every ill.” Today, too, he could triumph.

Shortly after 2:00 p.m., four more men walked quietly into the Roxy’s projection room and settled into the easy chairs. No one took much notice. They looked ordinary, not much different from the group already gathered there. The newcomers were fellow scribes, apparently, probably delayed by some last-minute piece of newsroom business.*

“I am William Fox,” one of the four newcomers began quietly. “This gentleman is Winfield Sheehan.”

Conversation immediately hushed. Fox had the sort of electrifying energy that changed everything—“the compelling force that made people do what he wanted,” according to one acquaintance.

Fox introduced the two other men in his group, “Mr. Nicholas Schenck and Mr. Bernstein.” Schenck was the president of Loew’s, Inc. David Bernstein, considered a financial genius, was Loew’s vice president. Both men had been with Loew’s since its beginning and had been close, trusted friends of Marcus Loew.

As pencils and pens hovered over notepads, Fox detoured into reminiscence. He never tired of telling this story. “All my savings were in it,” he explained, recalling his purchase twenty-five years earlier of his first theater, a 146-seater, at 700 Broadway in Brooklyn. “The second night I stood outside and wondered how to get customers. We weren’t doing a thing. Anybody could see I was downhearted.” After he hired a circus performer to do tricks on the sidewalk, Fox noted, everything changed. “Inside a week we had the place packed and were using police reserves.”

A few moments later, he snapped back to the present, asking that copies of his one-page, six-paragraph typed press release be passed around the room. Its language was subdued. “Fox Theatres Corporation has purchased a substantial block of the common stock of Loew’s Incorporated,” the statement began. “The officials and executives of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio in California will

continue in authority and the production personnel and activities will be unchanged.” Likewise, none of the policies or personnel of M-G-M’s parent company, Loew’s, would change. Neither of the terms takeover or merger was used. The rationale for the stock purchase, according to the press release, was simply to help Fox Theatres bring “a vastly improved quality of screen entertainment” to audiences worldwide.

Instantly, a barrage of questions assaulted Fox and his executive phalanx. They simply repeated information from the press release.

The reporters closed their notepads and rushed out to file their stories.

Now head of a $300 million empire with projected annual earnings of $15–$20 million, William Fox had just become the most powerful person in the worldwide motion picture industry. Expressing the majority opinion, the trade journal Exhibitors Herald-World applauded Fox’s “vision,” “energy,” and “consummate courage,” and gushed that the industry was lucky to have a leader who “has the future of motion pictures close at heart.”

In less than a year, Fox’s life would turn upside down and his once-masterful stroke in acquiring the Loew’s shares would be excoriated as the height of reckless folly—a greedy, self-destructive grab for power. Subsequent events, mired in the chaos and panic of the Great Depression, would destroy Fox’s motion picture career. Then film history buried him. If character is fate, then fate is character: All along he must have been the sort of person who deserved what eventually happened to him. He wasn’t worth remembering.

That simplification ignores enormous portions of the truth and cheats Fox of the complexity of his character and historical circumstances. In fact, he brilliantly transcended his times and also blindly fell victim to them. Yet what happened later does not change what went before. For all his pivotal contributions to the art, technology, and business of the movies, widely celebrated in his day, Fox was the greatest of all the studio founders. A fighter and a dreamer who relied on clear-eyed vision and an indomitable will, he did more than anyone else to make the movies what they are today.

The Man Who Made the Movies

The Man Who Made the Movies